I remember the relief I felt one day at university when our tutor told us that even the best artists cannot work without reference. It’s tempting sometimes, particularly if you’ve drawn something before, to look at it with a foppish wave of your hand and exclaim, “I can illustrate that, I know how it works.”

This can be a bit of a trap your mind sets for you: because you’ve seen a bird fly over your head thousands of times, you might think, “I know how to draw that, I don’t need any reference images to help.” But as soon as you try to replicate it, to draw or paint it yourself without something to refer to as a decent final artwork, you find the solid idea of that bird falls apart like a wet cake into different bits you remember, but may struggle to fit together as a whole. This can be incredibly frustrating to a person at any point in their artistic career, and can cause the throwing of pencils and other drawing materials across the room.

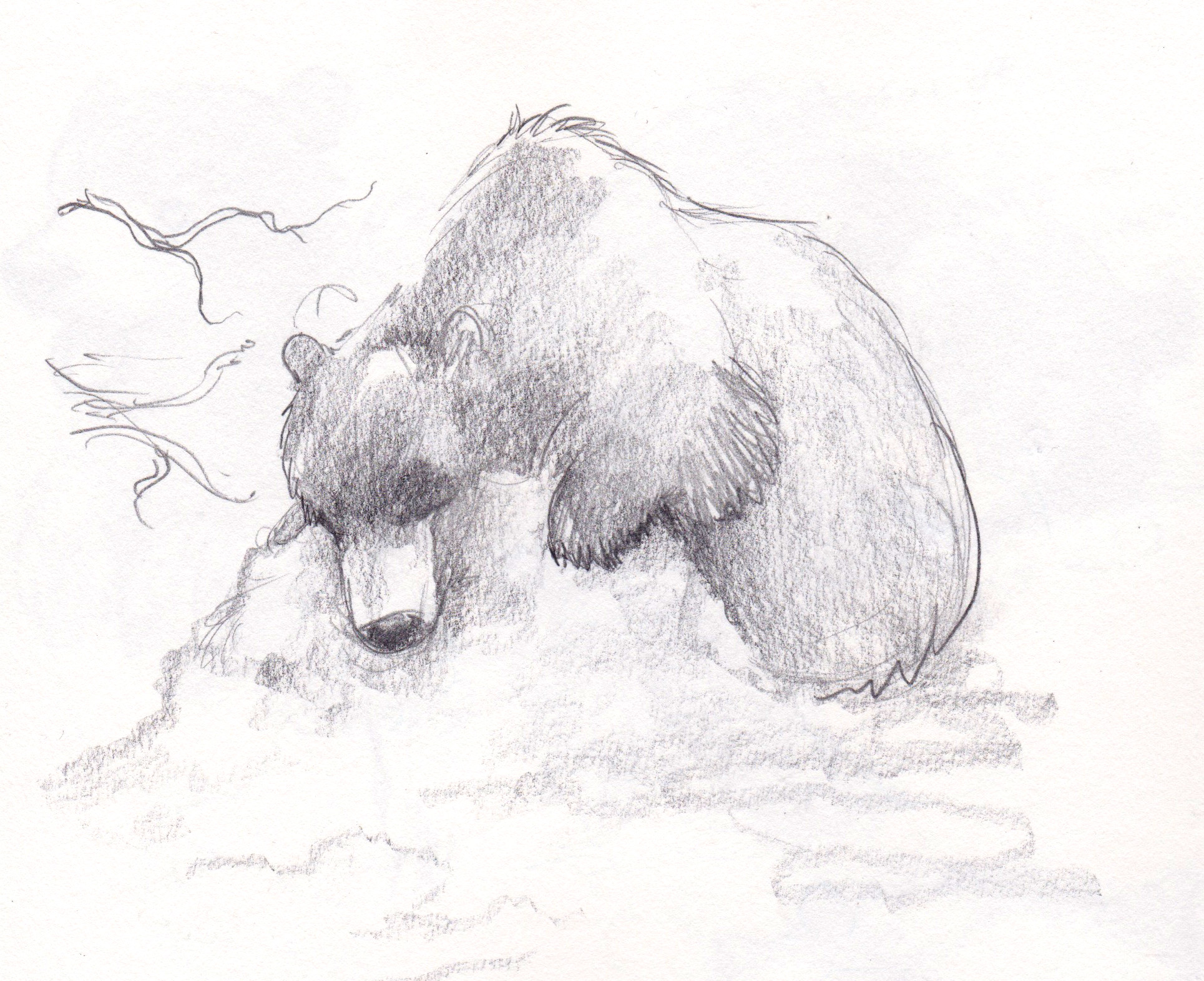

Those who read my blog regularly will remember in my last post my mentioning of a personal project I’ve been dedicating time to each week involving bears. I used to find drawing bears quite difficult- they are heavy, but since a lot of the weight that is visible is topped off with fur, it’s sometimes hard to tell where movement comes from, particularly from a static image. (I’ll confess, part of the reason I chose the characters for this project was down to the fact that I found bears a challenge.)

Of course, the best way to study movement is in real life, but unless I were to visit a zoo (where movement could easily be restricted due to lack of space) or go somewhere where bears exist naturally, it may be a little tricky. Certain places in Sweden have “hides” where photographers/artists can go to study bears without disturbing them- something I’d love to do, but it wouldn’t be that easy for me to just pop over there of an afternoon.

I’ve found that a fantastic resource for this project so far has been studying animated bear characters.

For an animator to create a moving sequence they have to know everything about how that person or creature will move and express itself. An animator will have had to pick apart their subject to understand how it works, which is perfect when it comes to our research, as it presents us with a comprehensive cross-section of all the parts that make up this or that.

Vimeo had some brilliant examples of this- Guillaume Arantes, a Gobelins 3D animation student, produced a fantastic cycle that showed a bear’s walk from four different angles. Below is a screenshot of his animation with the site address for those who might want to find it!

(All rights for the original sequence below belong to Guillaume Arantes.)

Pixar’s Brave also offered a large amount of inspiration in terms of creating two very different bear characters just by using different line weights and textures:

My character development is still in progress, but here is an early drawn sequence of what the little lad might look like:

Lots of round shapes with short and soft features and fluffy fur achieved with a soft 3B pencil definitely helps to establish his youngness.

Putting other objects in with the bear can help them come to life, as they appear to play before your eyes. Here Mama bear gently paws a balloon in the same way she might handle her cub.

I’ve approached their habitat in the same way, in terms of slowly picking it apart. A very good friend of mine lives in Norway and has been kind enough to keep me stocked with forest photos to study. Rocks, hideyholes, trees and paths have come under even more scrutiny than usual…

It’s a long process, but I love it!

The AutumnHobbit

© Carina Roberts and AutumnHobbit. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Carina Roberts and AutumnHobbit with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.